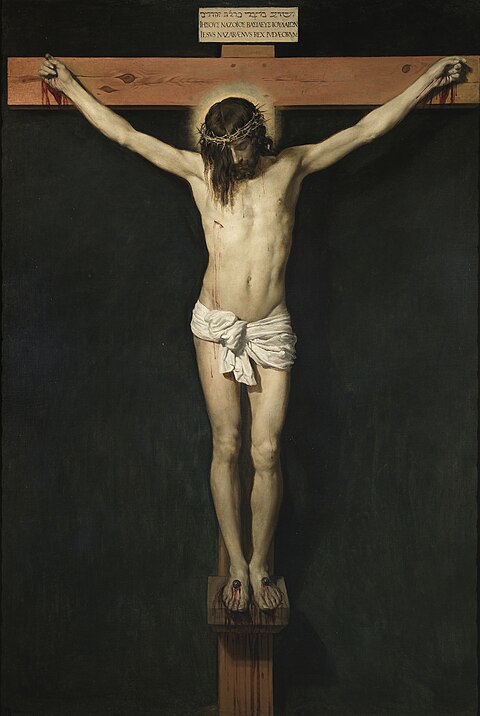

The music of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) demands much from its listeners. It is not simply something to be passively enjoyed; rather, it compels the audience to engage both spiritually and musically. Nowhere in Bach’s output is this more evident than in his Passions—musical settings of the most compelling narrative of the intersection between the divine and the human, in which God becomes flesh and dies on a cross for the sake of humanity. These works do not merely recount the story; they immerse the listener in an emotional and spiritual journey, where the depth of human suffering meets the promise of redemption.

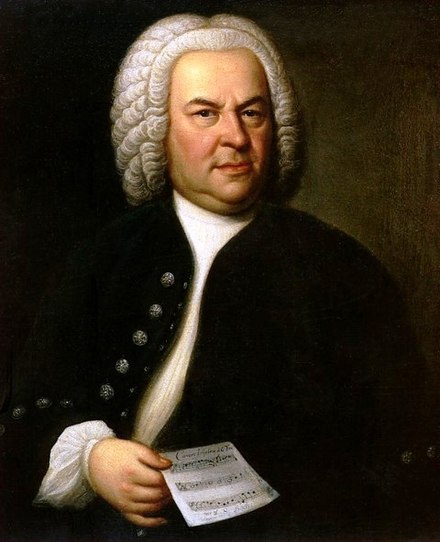

J.S. Bach

Bach was born into a musical family as the youngest of eight children in Eisenach, in what is now Germany. His career began at 18 when he was appointed court musician in the chapel of Duke Ernst III in Weimar, where his reputation as a keyboard player quickly grew. This led to a new position at a church in Arnstadt, but Bach became increasingly frustrated, frequently clashing with the authorities over the quality of musicians he was required to work with. He further angered his employers by taking an unauthorised four-week absence to walk 300 miles to Lübeck, to hear Dieterich Buxtehude play the organ.

Over the next several years, Bach held various posts, including a second tenure at the Weimar Court. This ended in 1717 when he was dismissed and briefly imprisoned for “too stubbornly forcing the issue of his dismissal.” He then moved to Köthen, where he worked for Prince Leopold, a fellow musician who valued his talent, provided generous compensation, and granted him significant artistic freedom. As a Calvinist, Leopold did not incorporate elaborate music into worship, and so much of Bach’s output during this period was secular, including the orchestral suites, cello suites, sonatas and partitas for solo violin, and the Brandenburg Concertos.

In 1723, Bach’s career took a pivotal turn when he was appointed Director of Church Music in Leipzig. His duties included overseeing the St. Thomas School Music and Latin teaching, and providing music for church services. Leaving what was arguably a comfortable position under Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Köthen for Leipzig was perhaps a testament to the depth of Bach’s faith, and a commitment to the vocation of teaching. He remained in Leipzig for the next 25 years. As was often the case, Bach frequently clashed with his employers, particularly over financial matters. In his final years, as his eyesight failed, he sought treatment from the British eye surgeon John Taylor, whose questionable methods ultimately proved fatal. Bach died on 28th July 1750 from complications arising from the unsuccessful procedure.

Liturgical Background

Bach was composing in post-Reformation Germany, in the wake of Martin Luther’s break with the Catholic Church. Luther taught that salvation was a gift from God, granted through faith alone rather than earned through good deeds. He rejected the traditional divide between clergy and laity, advocating instead for a universal “priesthood of all believers.” His translation of the Bible into German gave the laity greater access to scripture, reducing their reliance on what he viewed as a corrupt ecclesiastical authority. Luther believed that deep contemplation of Christ’s suffering and death was the true path to faith and a clear conscience. While religious observances like attending mass had value, he saw reflection on the cross as the most essential way to seek and experience God. Luther also saw music as a divine gift, placing great importance on its role in worship, particularly in congregational hymn singing. This religious framework influenced Bach’s composition of his two Passions: St. Matthew and St. John.

The Passions are presented in the style of an oratorio, a large-scale sacred choral work structured like an opera in terms of its musical style and dramatic form. The story is delivered through secco Recitative, text sung with speech like rhythms by ‘The Evangelist’, with Arias and choruses punctuating the story. The choruses, often portraying crowds, serve a purely dramatic function. Arias, by contrast, take us outside the immediate narrative, prompting reflection. For example, when Peter follows Jesus, the subsequent aria invites the congregation to consider that Christ’s call to follow him extends to each of us, urging us to respond with joy.

The inclusion of chorales (Lutheran hymns) adds another layer to the narrative, drawing the congregation into the story. For example, the first chorale in Bach’s Christmas Oratorio is the so-called “Passion Chorale,” compelling the congregation to reflect on Christ’s death and resurrection even as they celebrate his birth. In St. Matthew’s Passion, when the disciples ask, “Is it I?” (Bin ich’s?), the following chorale provides the answer from the congregation: “It is I” (Ich bins), acknowledging that it is through our sin that we betray Jesus. Likewise, in St. John’s Passion, after Peter denies Jesus, the chorale shifts the focus to us, reminding us that we too deny Christ through our sins and need forgiveness, just as Peter was.

St. John’s Passion draws its text directly from the Gospel of St. John, with Bach preserving the scriptural text without alteration. However, he incorporates two dramatic episodes from St. Matthew’s Passion. The first is Peter’s weeping upon hearing the cock crow, which powerfully captures the raw emotion of his denial. The second is the tearing of the temple veil after Jesus’ death, symbolising the removal of the barrier between the Jewish clergy and laity—an act that may have resonated with Bach’s own Lutheran beliefs. Bach’s intention here appears clear: to engage the congregation’s own emotions and beliefs, drawing them into the spiritual depth of the narrative.

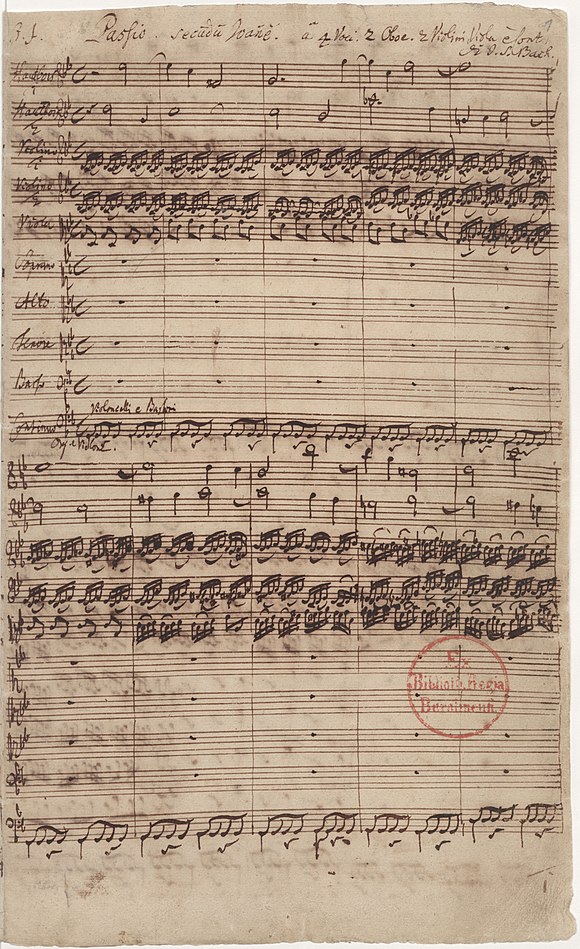

St John Passion

The work begins with one of Bach’s most poignant choruses, (Prologue: Herr, unser Herrscher, dessen Ruhm in allen Landen herrlich ist) immediately drawing us into a world rich with profound and layered emotions, where the complexities of human suffering and divine mystery converge. Crossing musical lines create a ‘Kreuz’ (Cross) motif, using dissonance to symbolise the agony of the cross. The theological theme is powerfully introduced: Show us by your Passion that you triumph even in the most profound humiliation. Through this, Bach frames St. John’s Passion as a testament to the ultimate victory of the cross.

It is Maundy Thursday, just after the Last Supper, and Jesus has taken his disciples to a garden to pray. However, Judas has betrayed him, and soldiers arrive to arrest him. Jesus asks, “Whom do you seek?” and the soldiers answer aggressively, “Jesus of Nazareth!” (Chorus: Jesum von Nazareth). The chorus represents the crowd of soldiers. Once more, Jesus asks, “Whom do you seek?” and again, the soldiers respond with hostility. Jesus replies that it is he whom they seek, and that his disciples ought to be left alone. Peter draws his sword and strikes off the ear of the high priest’s servant, but Jesus, remaining calm, tells Peter to sheath his sword, asking, “Shall I not take the path my Father has given me?” A chorale follows (Chorale: Dein Will’ gescheh’, Herr Gott, zugleich), expressing a desire to be as faithful to God’s will as Jesus.

Jesus is bound and taken to the priest’s court, leading into the first vocal aria, (Aria: Von den Stricken meiner Sünden) which relates how Christ was bound to allow us to be free of the chains of our sins. Peter follows Jesus, and another aria (Aria: Ich folge dir gleichfalls mit freudigen Schritten) affirms how we too will follow Jesus.

Jesus is being questioned by the high priests and is struck by one of the high priests’ officers. Jesus asks the officer “Why did you strike me?”- the following chorale (Chorale: Wer hat dich so geschlagen) questions, ‘Who wounded you?’- the second stanza answers: ‘Tis I have done this wounding by heedless sins’.

The crowd questions Peter’s association with Jesus (Chorus: Bist du nicht seiner Jünger einer?). Their staccato notes reflect a harsh and indifferent tone. Peter continues to deny his association with Jesus, and when the cock crows, the weight of his betrayal hits him, causing him to weep bitterly. The final aria of Part 1 is for the tenor (Aria: Ach, mein Sinn), and are the thoughts of Peter: “In my heart remains the pain of my misdeed, since the servant has denied the Lord.” The following chorale (Chorale: Petrus, der nicht denkt zurück) reminds us that we also deny Christ through our sins and need forgiveness. This ends the first part of the Passion.

Part 2 begins with a chorale (Chorale: Christus, der uns selig macht) which invites us back to the action, highlighting the importance of Jesus’ suffering being foretold in the Old Testament.

Jesus is then brought before the high priest Caiaphas and later taken to Pontius Pilate. Pilate asks, “What accusation bring ye against this man?”, expecting no answer. The crowd erupts, as if Jesus was innocent, then they would not have brought him (Chorus: Wäre dieser nicht ein Übeltäter, wir hätten dir ihn nicht überantwortet.). Pilate, finding no fault in Jesus, asks the crowd to judge Jesus using their own laws – but the crowd want to see Jesus killed, and reply demanding he be tried by the Roman laws instead (Chorus: Wir dürfen niemand töten.). Pilate then asks Jesus, “Are you the King of the Jews?” to which Jesus replies, “My kingdom is not of this world; if it were, my servants would fight.”. A chorale (Chorale: Ach großer König, groß zu allen Zeiten) asks us how we could be the servants that Jesus’ refers to.

Pilate offers the crowd a choice between Jesus, and Barabbas, a murderer. The crowd shout, “Not this man (Jesus), but Barabbas!” (Chorus: Nicht diesen, sondern Barrabam!). Pilate then orders Jesus to be whipped.

What follows is one of his most radiant, tender, and poetic ariosos ever written (Arioso: Betrachte, meine Seel’, mit ängstlichem Vergnügen). The text conveys that from Jesus’ suffering comes the greatest good: from the thorns that pierce him, beautiful flowers bloom; from the bitterness of his suffering, the sweetest fruits are grown.

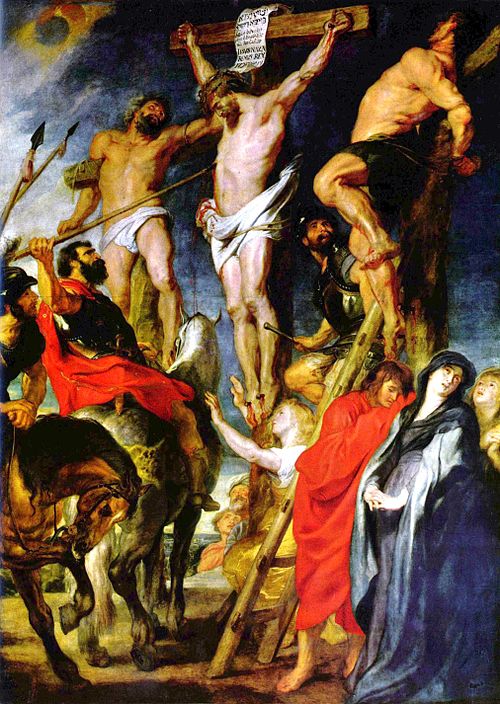

The soldiers crown Jesus with thorns and mock him in a chorus(Chorus: Sei gegrüßet, lieber Judenkönig). When the high priests and officers cry out for his death a fierce, fast-paced, and dissonant chorus follows (Chorus: Kreuzige, kreuzige!). The next chorus portrays the high priests rigidly upholding the law, with Bach adhering strictly to the rules of fugue, almost like a student showcasing his mastery of the form (Chorus: Wir haben ein Gesetz, und nach dem Gesetz soll er sterben).

The following chorale (Chorale: Durch dein Gefängnis, Gottes Sohn, muß uns die Freiheit kommen) symbolises the victory of the Cross, answering the plea made at the beginning of the work. To highlight the significance of this moment, Bach mirrors the structure of the surrounding movements—before and after the chorale, we hear two choruses with identical melodic material, and before and after that, the repeated calls for “Crucify Him!” This mirrored structure resembles a palindrome, conceivably symbolising the outstretched figure of Jesus on the cross, with the victory of the cross at its heart.

Pilate, still finding no fault in Jesus, seeks to release him, but the crowd is adamant that he be tried (Chorus: Lässest du diesen los, so bist du des Kaisers Freund nicht) and put to death (Chorus: Weg, weg mit dem, kreuzige ihn!). Pilate then asks the crowd “Shall I crucify your king?” to which the crowd respond that only Ceasar is the Kings (Chorus: Wir haben keinen König denn den Kaiser.).

Jesus is taken to Golgotha to be crucified. A bass aria with Chorus interjections (Aria: Eilt, ihr angefochtnen Seelen) asks people to hurry to Golgatha to witness the vicotry of the cross, to ease tormented souls. Pilate them writes a sign saying ‘Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews’ in different language, which continues to anger the crowd (Chorus: Schreibe nicht: der Juden König). A chorale (Chorale: In meines Herzens Grunde) puts further emphasis on the joy in Jesus sacrifice for humanity’s sake.

Jesus’ clothing is torn apart, and soldiers cast lots for Jesus’ coat. Bach introduces an unexpected chorus, filled with playful, quick running notes and syncopations (Chorus: Lasset uns den nicht zerteilen, sondern darum losen, wes er sein soll.). This light-hearted music contrasts sharply with the weight of the surrounding events, emphasising the disconnect between those who understand the significance of the moment and those absorbed in the trivialities of everyday life. Jesus’ disciples, and his mother, do understand the significance, and remain at Jesus’ side and a Chorale (Chorale: Er nahm alles wohl in acht) invites us to stand by Jesus’ cross.

Jesus utters his final words: “It is finished”, signalling the fulfilment of his mission. An aria proclaims the joy of the victory of the cross, in juxtaposition to solemnity of the scene (Aria: Es ist vollbracht!). Another bass aria, this time with a choral chorale, (Aria: Mein teurer Heiland, laß dich fragen) poses to Jesus whether his death has saved hummanity- Jesus’ replies, bowing his head, with a simple ‘Ja’ (Yes). At the moment of his death, the veil of the temple is torn in two, the earth quakes, and saints are risen. Firstly, a Tenor Arioso (Arioso: Mein Herz, in dem die ganze Welt bei Jesu Leiden gleichfalls leidet) questions our own hearts- Jesus’ death has caused rocks to split, what ought our hearts do at this news?. Secondly. an alto aria gravely reflects upon Jesus suffering declaring with increasing repetition of Jesus’ death. Having learnt of his death, we ask in a chorale to learn from the narrative (Chorale: O hilf, Christe, Gottes Sohn).

The sublime final chorus (Chorus:Ruht wohl, ihr heiligen Gebeine) serves as a bookend, concluding solemnly in C Minor. Bach adds a post-script—a closing chorale, (Chorale: Ach Herr, lass dein’ lieb’ Engelein) a prayer from the faithful: “Lord, when I die, send your angels to take me to Abraham’s bosom where there is no pain. Then, at the last day, wake me from sleep so that I may see you. I glorify you eternally!”.

Bach’s setting of the Passion presents a deeply compassionate and hopeful narrative, where the crucifixion is portrayed as an act of redemptive love, and the resurrection is awaited with unwavering certainty.

Samuel Foxon, March 2025

If you wish to use or adapt any part of these notes, please do get in touch!

Leave a Reply