Preconceptions can be deceiving. The title ‘King Arthur (Or the British Worthy): An Opera in Five Acts’ might lead the listener to some assumptions.

‘King Arthur’ evokes familiar names like Guinevere, Lancelot, or Gawain. This tale is different. We depart from Camelot and the Round Table, but keep the magic, the conflict, and the timeless struggle between good and evil. At the centre stands the noble King Arthur, guided by the wisdom of the sorcerer Merlin and aided by Merlin’s ethereal spirit companion, Philadel. Their quest is to defend Britain against the invading Saxon King Oswald, whose ambitions are supported by his own sorcerer, Osmond, and the sinister spirit Grimbald. We also have some unexpected guest appearances from mythology — Cupid and Venus — creating a Restoration era spectacle.

Describing King Arthur as an opera may also seem unusual — after all, Henry Purcell (1659-1695) is often credited with only one “true” opera, Dido and Aeneas, which tells a story through the medium of the voice. In the seventeenth century, the term ‘opera’ encompassed a broader theatrical tradition. Today, we would use the term semi-opera to describe King Arthur, which is a uniquely English blend of spoken drama, music, dance, and of course, spectacle.

Whilst today’s performance forgoes staging, actors, and dancing, the spectacle remains. The storytelling rests in the capable hands of our narrator, allowing the music to be brought to life…

Historical Background

The Restoration era witnessed an explosion of artistic expression. Under Oliver Cromwell’s interregnum, theatre, music, dance, and other forms of entertainment had been suppressed, but with the return of Charles II (“The Party King”) to the throne, these once-taboo arts flourished once more. Charles II had spent his exile in France and enjoyed the finer things that the Baroque lifestyle offered, including lavish operas. Ideas from Roman and Greek mythology, rediscovered during the Renaissance, had become highly valued by the time of the Restoration, where knowledge of the classics was seen as a mark of sophistication and cultural refinement.

Henry Purcell was born in Westminster in 1659 and began his musical training as a chorister under Henry Cooke, the musician appointed by Charles II to restore the musical excellence of the Chapel Royal. Purcell later studied with Pelham Humfrey, himself a student of Jean-Baptiste Lully, the influential court composer to King Louis XIV of France. Though Italian by birth, Lully was instrumental in shaping the French Baroque style, particularly through his operas, many of which paid homage to King Louis’ styling as the “Sun King”. Through this lineage, a distinct French flavour found its way into the emerging English musical tradition.

As Purcell grew into a highly accomplished musician, he not only composed for the Chapel Royal but also created a wealth of secular music, including incidental music for plays. In 1689, he composed his renowned opera Dido and Aeneas, and in 1691 he wrote the music for King Arthur and The Fairy Queen, the latter being an adaptation of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Purcell’s musical output is remarkable given that he died at the young age of 36, in the November of 1695. One theory surrounding his untimely death suggests that he caught pneumonia after returning home late from the inn, only to find that his wife had locked him out — another theory is that he suffered from Tuberculosis.

Being such an accomplished composer, Purcell worked with the best playwrights of the time, including John Dryden (1631-1700), who was Britain’s first Poet Laureate. Dryden initially began writing King Arthur as a piece of political propaganda in support of Charles II. However, work on the piece ceased after the King’s death, as the play was now politically impertinent. The Glorious Revolution of 1689 deposed King James II, making way for the protestants William and Mary, and allowing the work of King Arthur to be dusted off and reworked – this time with Henry Purcell to provide the music.

In his preface, Dryden made a deliberate effort to assure the new royal censors that King Arthur was free of any politically sensitive content. He emphasised the fairy-tale nature of the story, presenting it as a whimsical fantasy. As a Tory (that is to say, a staunch supporter of James II’s claim to the throne), Dryden likely harboured little affection for William and Mary. The play’s alternative title, The British Worthy, invites us to ask, “Who is truly worthy of the British throne?”. In the drama, it is King Arthur who triumphs over Oswald, who is sent back to his foreign homeland. In Dryden’s time, this question could be equally applied to the struggle between King James II and the foreign monarchs, William and Mary.

Dryden believed that only supernatural beings, their followers, shepherds, and servants were truly fit to express themselves through song. As a result, the key actions involving the main characters — King Arthur, Merlin, and the love interest Emmeline — are conveyed not through music, but through spoken dialogue. In today’s performance, this role is taken up by the narrator.

The Plot

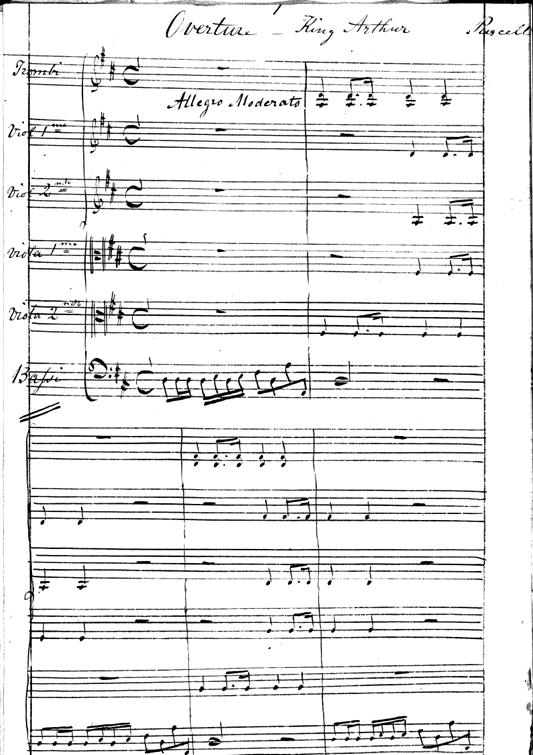

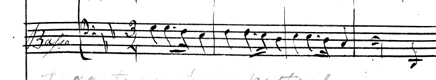

We begin with a set of Overtures, which would have been used to introduce dignitary members of the audience and set the scene. Notably, one of the overtures is in the French style, in a stately tempo with over dotted rhythms (Notes Inégales) leading into a fugal work.

Act 1

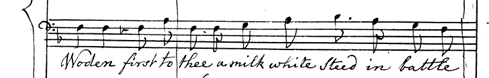

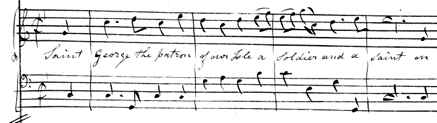

King Arthur, Britain’s noble leader, seeks to marry the blind Emmeline, cherished heiress of Cornwall. However, this union is contested by the Saxon Lord Oswald, who also desires her hand. Both leaders call upon their armies to decide the outcome in a brutal battle. Arthur’s forces find strength in their prayers to St George, while the Saxons turn to ominous rituals, including sacrifices and rune casting.

Act 2

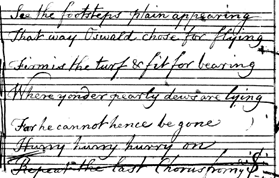

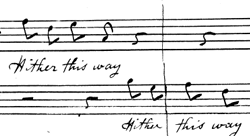

Philadel warns Merlin of Grimbald’s plot to lead the Britons to their doom by feigning a Saxon retreat toward the cliffs. Merlin tasks Philadel and their spirit allies with safeguarding the Britons and foiling Grimbald’s plan before departing in his chariot. With some to-ing and fro-ing, the spirits try to lure King Arthur away from one another.

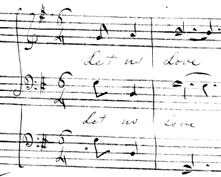

Emmeline seeks refuge during a raging battle, praying for Arthur’s safety. She loves Arthur for his noble mind, and he reciprocates her love with unwavering devotion, showering her with romantic gestures like poems, songs, and gifts. A pastoral interlude is presented, offering a glimpse into the carefree serenity that a bucolic existence bestows.

Act 3

Osmond, a deceitful ally of Oswald, abducts Emmeline in Oswald’s absence. Initially planning to seduce her by force, Osmond reconsiders, believing he can win her favour despite his hideous appearance, as Emmeline is blind. To charm her, he stages a masque with Cupid melting a frozen ruler’s icy heart, symbolising his hope to win her favour — though his confidence may be misplaced. Purcell captures the freezing with a shivering effect: a trill on every note. Lully utilised a similar effect in his opera Isis, but Purcell has perfected the technique with a chromatic harmony and rising melodic lines. Whilst seeking Emmeline, Philadel is captured by Grimbald but escapes and casts a spell on him. Merlin and Arthur arrive, with Merlin giving Philadel a vial to restore Emmeline’s sight before heading off to dispel the forest’s dark enchantments.

Act 4

Forewarned of illusions by Merlin, Arthur ventures alone into the woods, guarded by Philadel, who can unveil evil spirits with Merlin’s wand. Instead of expected horrors, Arthur hears music and two sirens appear, urging him to lay down his sword. Purcell writes this as a Passacaglia, an extensive composition characterised by a short, repeated ground bass in triple metre.

King Arthur resists their temptations and presses on. Nymphs and sylvans emerge, dancing to harmonious songs. A vision of Emmeline appears from a tree trunk, urging Arthur to relinquish his sword. Philadel reveals the illusion as Grimbald, and Arthur fells the tree, breaking the enchantments and clearing the path to the Saxon fortress. Grimbald is bound by Philadel and brought into daylight.

Act 5

The Britons reach the Saxon fortress, where Oswald proposes single combat against Arthur. After a fierce battle, with the magicians duelling alongside, Arthur disarms Oswald but spares his life. Trumpets announce Arthur’s victory as he commands Oswald to return to Saxony. Emmeline is restored to him, Merlin imprisons Osmond, and British sovereignty, faith, and love are proclaimed.

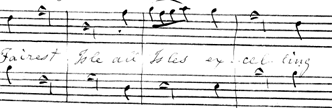

With harmony restored and King Arthur’s sovereignty secured, the revelries can commence. This includes a scene at an inn, lovers coming together, and ‘Fairest Isle’, a much beloved aria that moved the hymn writer Charles Wesley to write the words to the famous hymn ‘Love Divine, All Loves Excelling’ to its tune 50 years later.

Samuel Foxon, April 2025

If you wish to use or adapt any part of these notes, please do get in touch!

Leave a Reply