The Choral repertoire is dominated by music of the Church – as daily life across the centuries was too. From this wealth of music, we can glean insight into the relationship that the generations before us had with the divine, through joy and through strife. With faith comes piousness, a sense of purpose as part of a wider plan, and optimism for a better future. These have often been handed down to the masses from an elite and controlling church. Whilst fascinating, it tells little of the day to day lives people led. Outside the Church, people’s secular lives are now as they have always been – full of love and pain, and often a little bit naughty. This is the joy of secular music – it taps into the run-of-the-mill emotions of the run-of-the-mill people. The madrigal is a form of secular vocal music that flourished during the Renaissance period. The Italian madrigal emerged in the 16th century and reached its peak of popularity in the late Renaissance.

The inception of the Italian madrigal can be traced back to the vibrant cultural milieu of Renaissance Italy, particularly in cities like Venice. In the early 16th century, Venice emerged as a bustling centre of trade, commerce, and artistic exchange, attracting scholars, musicians, and wealthy patrons from across Europe. It was within this dynamic environment that the madrigal began to take shape, drawing influences from various musical traditions, including the Franco-Flemish polyphonic style and the Italian poetic tradition. The publication of collections such as Philippe Verdelot’s “Primo libro di madrigali” in 1530 marked the formal beginning of the genre, laying the groundwork for its subsequent development. As Venice continued to flourish as a cultural hub, the madrigal proliferated rapidly throughout Italy and beyond, following the trade routes that initially allowed it to flourish.

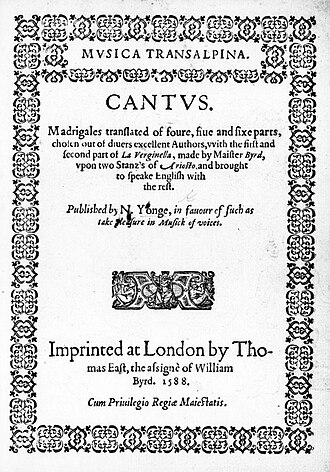

One such destination of the Italian Madrigal was England. During the 16th century, England witnessed a surge of interest in the Italian madrigal, spurred by diplomatic and trade connections with continental Europe. English composers, intrigued by the expressive possibilities of the form, began experimenting with their own adaptations, drawing on Italian models while infusing their compositions with distinctively English characteristics. The publication of Nicholas Yonge’s “Musica Transalpina” in 1588, featuring English translations of Italian madrigals alongside original compositions by English composers, marked a watershed moment in the Madrigal’s proliferation. The popularity of the English madrigal soared, buoyed by the flourishing music publishing industry for the working classes, and the patronage of nobility and affluent citizens. As the genre continued to evolve, it became an integral part of the English musical landscape leaving a legacy that still attracts composers today.

Our concert opens with La Tricotea, of unknown origin, but attributed to the equally enigmatic Franco Alonso of the Franco-Flemish tradition. The song is largely nonsense, mixing Spanish, pseudo-Spanish, French, Italian, and for lack of a better term – gibberish. This is perhaps fitting for a piece that would likely have been sung in a tavern, under the influence of Bacchus, the god of wine. The madrigal is lively in nature and quite reminiscent of a modern-day tongue twister.

Orlando Gibbons (1583 – 1625) is an eminent English composer and organist, and enjoyed patronages from those close to the Crown. He composed many madrigals and lute songs alongside anthems for the Church. As someone who made his wealth on the success of the Madrigal, he was somewhat resistant to the changing fashions to other forms of secular music The Silver Swan is said to be a lament of the madrigal genre. Based on the Apocryphal belief that, unlike songbirds, swans only sing on their death bed – hence the expression ‘Swansong’. Orlando Gibbons is said to have written this madrigal in recognition that the art form was dying out – and so the last line ‘More geese than swans now live: more fools than wise’ is a cutting criticism on the folly of man – or at least terms of this one type of secular choral music.

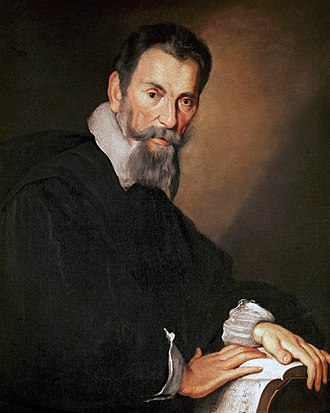

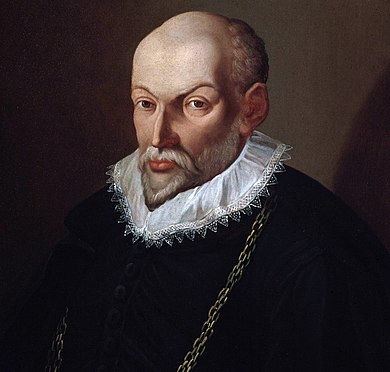

Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) is perhaps the best known and most celebrated of Italian choral composers, being a key figure in the move from the Renaissance to the Baroque eras of music. He was based in Mantua in the late 1590s, under the generous patronage of the aristocratic Gonzaga family. Montiverdi’s many publications were cutting edge, and thus so formative to the foundations of the rules of Harmony we know today. A notable example from his first book of madrigals is the exquisite Baci soavi e cari. The theme of this madrigal centres on kissing, highlighting the longing for kisses and the sweetness they bring. The repeated references to both kisses (baci) and death (morire) allude to the euphemistic “little death” (Petite Mort) well understood in the 16th century. In this context, the madrigal expresses a desire for the pleasure derived from kissing, a pleasure that, unlike death, is eagerly sought by lovers.

Thomas Morely was one of the most influential composers of English Madrigals, borrowing heavily from the Italianate masters. April is in my mistress Face is a translation of an Italian text full of seasonal references. The mistress is described with many seasonal references – her face youthful like April, her eyes bright like July, her bosom is generous like the September Harvest. However, her heart is likened to a Cold December, and the music takes a shift to a darker tonality.

Anima dolorosa comes from Monteverdi’s fourth book of madrigals, which delves into more cerebral and spiritual themes compared to the pastoral and sensual compositions of his earlier works. This madrigal portrays a tormented soul enduring and perishing in a hell of unending sorrow. Unlike the titillating notions of death in Baci soavi e cari and Ohimè, se tanto amate, this piece presents a profound and poignant death. The final lines are: “Why do you thrive on death? Consume the grief that now consumes you, of this death that, like life, is now leaving. Die, miserly one, in your death dying.”

A quiet melancholy shrouds many of the songs of the English Renaissance composer, lutenist, and singer John Dowland (1563-1626). Possibly due to his Catholicism, Dowland was denied employment in the court of Elizabeth I, leading him to work in France and later at the court of Christian IV of Denmark, where he gained considerable fame. In 1606, Dowland returned to England and secured a position in the court of James VI of Scotland and I of England. Weep You No More, Sad Fountains is quintessential Dowland, characterized by its languishing harmony and melancholic lyrics. Dowland delves into profound despair, pleading for sleep as a respite from sorrow.

Ohimè, se tanto amateis an example of Montiverdi’s work in the more developed style of the seconda pratica. Its emotional intensity (arising partly from daring use of dissonance) must have made it seem very ‘modern’, even shocking, to people accustomed to the late Renaissance style. Whilst musically, it is more mature and considered than Baci soavi e cari, the subject matter is not. Ohimè is a sigh– the sigh that would accompany the hedonistic pleasures associated with the aforementioned double-entendre of death. It is repeated incessantly and treated like an onomatopoeia – certain to raise the pulses of the 16th Century audience.

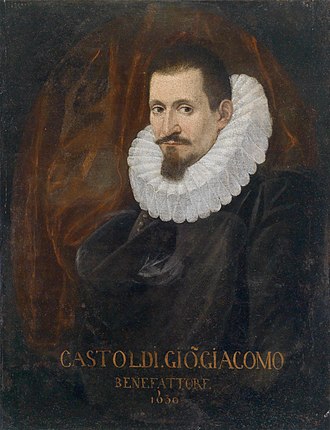

Our second half begins with the light-hearted Amor vittorioso. An eminent Italian composer of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, Giovanni Giacomo Gastoldi created a madrigal style known as the ‘balletto’ with the publication of his Balletti a cinque voci in 1591. This light genre is characterized by the vivacious, homophonic style and simple harmonies. As indicated by the name, these pieces were meant for dancing and can be easily identified by the “fa-la-la” refrains and the AABB phrase structure. They became very popular especially in England where such composers imitated (and even pirated) the words and music for their own madrigals. “Fa-la-la” invites the listener to imagine their own ending to each phrase – as innocent or debauched as they see fit.

Fair Phyllis is an English Madrigal by the composer John Farmer. The song depicts a somewhat voyeuristic pastoral scene where we observe Phyllis tending to her sheep while her lover, Amyntas, searches for her, wandering through the hills. Eventually, he finds her, and they fall down and start kissing. The lyrics contain a humorous and ribald twist with the phrase “up and down he wandered.” Initially, this suggests a game of hide-and-seek, but the second instance alludes to the act of kissing itself.

At first glance, Matona, mia cara by Orlando Lasso, seems too polite to contain anything improper, with its gently lilting refrain ‘Don Don, Diridiri Don’. The text is sung from the perspective of a German soldier who speaks very little Italian, yet still longs for the Italian ladies he meets. This is humorously conveyed in the lyrics, which include some French words the soldier mistakes for Italian, such as bon and compagnon – and follere, a word that means nothing in Italian but closely resembles a particularly vulgar verb. The soldier soon exhausts his polite vocabulary and resorts to direct and vulgar descriptions of his desires.

Borrowing once again from the Italian Masters, Thomas Morley has been inspired by Gastoldi in the charming My bonny lass she smilithhas more to it than meets the eye. Whilst we are familiar with bonny meaning attractive or as in the Scottish dialect, the usage here is probably the meaning that still exists in Midlands and Northern accents meaning fulsome or plump (N.b. Bonnie Prince Charlie is described as in the former) Morely is wearing his heart on his sleeve with his amorous intentions – although leaving just enough to the imagination with the refrain of “Fa-la-la”.

Arcadelt was a composer in the franco-flemish style. Ahimè, ahimè dov’è’l bel viso sighs at the loss of love to (a literal) death. It is easy to forget how common place death was to the generations before, and Arcadelt’s setting of this poem bares the raw emotions of losing a loved one.

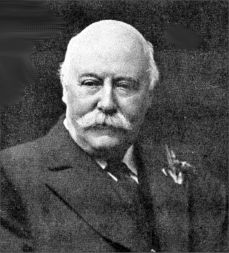

The secular madrigal enticed many a 20th Century composer, looking back with increased interest in the musical heritage of England, which saw a resurgence. Hubert Parry was once such composer. In Music when such Voices Die, Parry explores how sounds, sights, smells, and emotions can linger in our memories and be vividly reawakened long after the experiences themselves have passed.

The evolving harmonic language of Monteverdi faced significant criticism, particularly from Giovanni Maria Artusi in 1600. Artusi argued that the madrigal had become a monstrosity due to frequent changes to unrelated keys, resulting in modal incoherence. O Mirtillo from Monteverdi’s fifth book of madrigals exemplifies this with its jarring harmonic progression on the words Crudelissima Amarilli (cruellest Amarillis). In this piece, Amaryllis loves Mirtillo but must reject him because she is already promised to a deity, leading Mirtillo to believe his love is unrequited. Like many of Monteverdi’s later madrigals, the theme of love is depicted as dichotomous—Amaryllis/Love is both beautiful and fierce. Even the name Amaryllis has a dual meaning, as the Italian prefix amar- is the root of both love (Amore) and bitterness (Amara).

Now is the month of maying is one of the most famous of the English balletts written by Thomas Morley and published in 1595. The song delights in bawdy double-entendre. It is apparently about spring dancing the barley-break but is suggested that this might be more about rolling around in the hay. Yet again, a vibrant and polyphonic ’Fa-la-la’ can be substituted with something lewder.

Leave a Reply