Handel and the Oratorio

In 1741, George Frederic Handel (born in 1685) found himself facing a period of personal and professional struggle. Italianate operas were losing popularity, leaving Handel reliant on a limited circle of wealthy patrons, and grappling with financial difficulties. It must have been a relief for him to receive a well-crafted libretto from Charles Jennens, a wealthy Englishman and devout Christian. Handel would use this libretto to create what is arguably his magnum opus. The text consisted of biblical passages narrating the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, appealing to a universal audience. Inspired by Jennens’ text, Handel embarked on composing the music for Messiah, remarkably completing the entire oratorio in just 24 days.

The history of the oratorio genre can be traced back to the creation of opera. Opera evolved from the works of composers like Claudio Monteverdi in Venice and gained popularity across Europe. Composers, including Handel’s contemporary J.S. Bach (born in 1685), incorporated opera forms into their cantatas. While Bach excelled in music for the Lutheran Church, Handel became known for his secular operas. After training as a musician in his hometown of Halle, Handel composed four German-language operas in Hamburg. In 1703, he was invited to Italy, to contribute to making Florence a hub of opera in Italy. There, he composed his first Italian-language opera, Rodrigo, in 1707, along with Dixit Dominus, a work beloved by choral singers. In 1710, Handel took his opera Rinaldo (perhaps his best-known work and certainly a favourite of Handel himself) to London, where he eventually settled in 1712.

Oratorio, an art form that merged elements of Italian opera, including arias (songs) and recitative (speech-like singing to advance the plot), with sacred text, emerged. Unlike opera, oratorio was not dramatised, befitting the sacred nature of the text. Handel’s first oratorio, Il trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno, was composed in 1707 while Handel still lived in Italy. In 1736, with a waning interest in Italianate opera, Handel turned to oratorio to sustain his career. Oratorios were more cost-effective to stage, requiring no elaborate costumes, sets, or choreography, while providing audiences with a sense of spiritual fulfillment that secular operas couldn’t match. Handel achieved limited success with works like Saul and Israel in Egypt, which borrowed elements from his earlier compositions.

Messiah

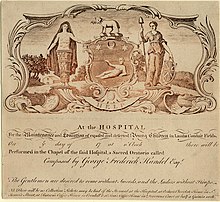

In the summer of 1741, Handel was invited to Dublin by the 3rd Duke of Devonshire and encouraged to compose an oratorio for a benefit concert supporting local hospitals. In writing Messiah in such a short space of time, Handel repurposed arias from previous operas, and the score is littered with mistakes and blots. Messiah narrates the birth, life, death, and subsequent resurrection of Jesus. The premiere took place in the spring of 1742 at ‘The Great Music Hall’ in Dublin, with proceeds benefiting two hospitals and a debtor’s charity. Handel conducted from the Harpsichord. Messiah was an immediate success – gentlemen were asked to remove their swords, whilst Ladies were asked to not wear hooped dresses to allow the largest possible audience. Of course, we hope our audience extends the same courtesy today.

There is no definitive version of Messiah, as Handel wrote and rewrote movements to suit the soloists available. Over time, adaptations have been made, including a famous re-orchestration by Mozart in 1789, three decades after Handel’s passing. Present-day performances, often centered around the Christmas season, typically emphasise Part I.

Part I commences with Old Testament prophecies about the Messiah and coming salvation, followed by the story of Jesus’ birth. It opens with a French-style Overture characterised by over-dotted rhythms and a fugue. The tenor soloist delivers the first prophecy, “Comfort Ye, my People,” with other prophecies sung by a soprano “But who may abide”. The chorus presents the rousing Old testament prophecies “And the Glory of the Lord” and “For unto us a child is born.” A pastoral symphony sets the scene for the birth of Jesus, beginning in the fields. A soprano soloist guides us through the story, culminating in the choruses “Glory to God in the highest” and “His Yoke is Easy.”

Part II recounts the Passion, death, and resurrection of Christ. Handel uses declamatory fugal entries to set a tragic tone in “Behold the Lamb of God.” A series of mainly short choral movements covers Christ’s Passion, Crucifixion, Death, and Resurrection, concluding with the famous “Hallelujah Chorus.” While there are numerous apocryphal stories regarding the tradition of standing for the “Hallelujah” chorus, usually centring around a tardy or uncomfortable King Geroge II, there is no conclusive evidence of the king’s presence, and the first recorded mention of the practice dates back to a letter in 1756, three years before Handel’s death. This tradition has persisted, and with no compelling reason against it, we invite tonight’s audience to participate.

Part III invites the audience to contemplate the promise of eternal life, with the self-assured soprano solo “I know that my Redeemer liveth,” and the theatrical “The Trumpet Shall Sound,” culminating in “Worthy is the Lamb” with its rapturous “Amen.”

There is no doubt that Handel’s Messiah has earned its place as one of the most cherished pieces in the choral repertoire. For many, Christmas can’t truly begin until they’ve heard this soul-lifting masterpiece.

Leave a Reply