The narrative surrounding Mozart’s Requiem is steeped in intrigue and drama. In the twilight year of 1791, an enigmatic commission landed in Mozart’s hands. An Austrian aristocrat desired a Requiem Mass (Catholic Mass for the Dead) to be composed in memory of his departed wife, and he would compensate generously for it. The commission arrived via a discreet messenger, concealing the identity of the patron.

It remains uncertain if Mozart harboured suspicions regarding the benefactor’s identity, rumoured to be Count Franz von Walsegg-Stuppach, grieving the loss of his beloved Anna at a mere 20 years old. It is unclear whether Mozart was aware of rumours suggesting the Count’s intention to present the work as his own. Mozart was offered a sum of 225 florins, with half the payment upfront and the promise of the remainder upon completion a sufficient amount to discourage inquiries into the paymaster’s identity.

At the time, Mozart was amidst composing Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute) when he received a significant commission to create a serious opera, La clemenza di Tito (The Clemency of Titus), for the coronation of Leopold II as King of Bohemia. Despite this interruption, Mozart fervently composed La clemenza di Tito during August, journeying to Prague by month’s end to conduct its premiere on September 6. Following this, he swiftly returned to Vienna to complete Die Zauberflöte, adding two final numbers just before its grand premiere on September 30.

Only then could he divert his attention to the Requiem Mass. However, Mozart was now grappling with serious illness, necessitating him to dictate portions of his compositions to an assistant. A deeply superstitious man, Mozart became unsettled by the mysterious commission and confided in his Wife, Constanze, believing he was composing his own Requiem Mass. And indeed, he was, for he passed away on December 5th, 1791, at a mere 35 years of age. In a romantic injustice, his Requiem remained unfinished.

The grieving Constanze feared that the incomplete commission would entail reimbursing the substantial sum already received, and she was eager to ensure the completion of her late husband’s final composition.

Constanze enlisted the help of several of Mozart’s students to finalize the Requiem. Initially, she approached Joseph Eybler to orchestrate incomplete sections with limited success. The bulk of the task fell upon the 25-year-old Franz Xaver Süssmayr. By completing Mozart’s work, Süssmayr (an obscure composer, whose other surviving works have since been deemed to be of little merit) ensured that he would always be mentioned in the same breath as Mozart – whether this is fame or infamy is debatable.

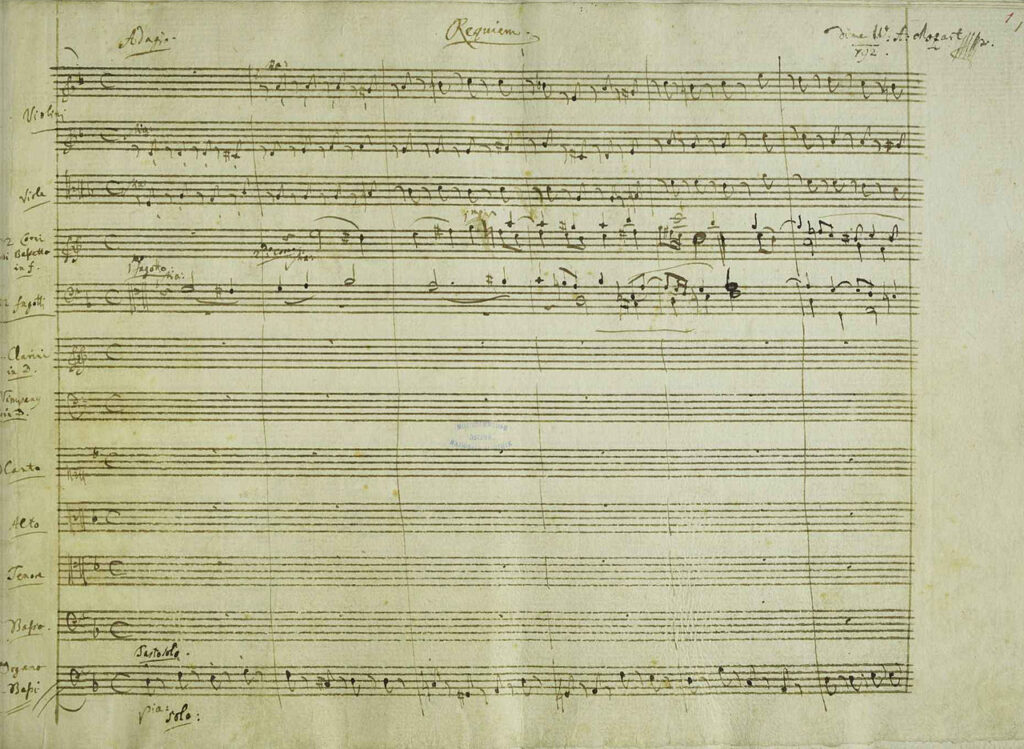

Of the twelve movements comprising the Requiem, Mozart had only managed to complete the opening Kyrie entirely. For most others, he had penned the vocal parts along with a figured bass line, providing clear indications for harmony and orchestration. Curiously, Mozart delayed composing the seventh movement, the Lacrymosa, until after completing movements eight and nine, but he only managed to jot down the first eight bars before his passing. Additionally, he left behind various fragments on scraps of manuscripts, including the trombone solo at the beginning of the Tuba Mirum. Süssmayr assumed the responsibility of completing the Lacrymosa as well as the final three movements – reprising Mozart’s own music from the opening, an idea which, according to Constanze, Mozart himself had suggested. After Süssmayr finished the piece, he transcribed a new score to avoid arousing suspicion of its multiple composers; he forged Mozart’s signature and dated the manuscript 1792.

The intrigue and mystery attached to the story has captivated many individuals to complete Mozart’s Requiem themselves, among them Duncan Druce. Druce was a highly esteemed performer, composer, and musicologist in both the avant-garde and early music circles. As a skilled composer of counterpoint and an adept writer of pastiche music, he was drawn to Mozart’s requiem, remarking:

‘Whilst the work as a whole has proven to be one of Mozart’s best-loved and most admired, it has been clear ever since [Süssmayr’s completion] was first published that it sometimes lacks the perfection of detail, smooth craftsmanship, the imaginative relationship of subsidiary material to the whole that is so characteristic of Mozart’s other mature masterpieces. Süssmayr’s orchestration may not often impede Mozart’s vision, but it rarely enhances it.’

This led to Druce completing his own rendition of Mozart’s requiem in 1984, which was subsequently performed at the Proms in 1991 to great acclaim. By 1993, it was being published by Novello, which they continue to do to this day. The most notable addition is an extended ‘Amen’ in the style of a double fugue, following the Lacrymosa. Mozart had sketched out the parts for the opening – Süssmayr had omitted it.

By performing Druce’s rendition of Mozart’s requiem, it is hoped that audiences (and of course musicians) will be able to experience the Requiem as if for the first time.

Critical Commentary

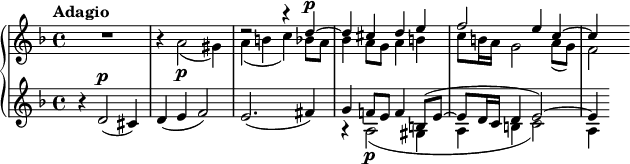

The opening Introitus, the only section fully authored by Mozart, begins with the chorus pleading for eternal rest, followed by the soprano soloist singing the first psalm. In the Kyrie, Mozart shows his skills as a writer of counterpoint, as he introduces the first fugue of the Requiem. In a striking departure from the expected, Mozart concludes with a perfect fifth instead of the expected major or minor third, lending an austere conclusion.

The heart of the Requiem lies in the Sequenz, comprising of six movements alternating between chorus and solo voices.

The intense Dies Irae vividly portrays the Day of Judgement, while the Tuba mirum invokes scripture’s trumpet and its awe-inspiring call to judgement. Each soloist articulates nuanced emotions surrounding the Day of Wrath before converging as a quartet. While the chorus conveys the grandeur of judgement, the soloists express individual anguish. The chorus movement, Rex tremendae, follows in similarly vast operatic tone- then suddenly, a shift occurs: the dynamics diminish to piano, and the choir implores, ‘Save me, O fountain of mercy!’.

In the intimate pleading of the Recordare, each soloist offers a personal petition to God. The thundering full choir in Confutatis juxtaposes images of the damned engulfed in the flames of hell with that of a supplicant kneeling in prayer.

The Sequenz reaches its height with the Lacrimosa, a poignant lament for humanity on the brink of decision. The subsequent Amen, written in the style of a double Fugue brings a fiery conclusion to the Sequenz.

The Offertorium begins with Domine Jesu is a highly charged movement characterized by rapid contrasts and sudden outbursts. A brief solo quartet provides a temporary calm before the vigorous choral fugue ‘Quam olim Abrahae,’. Hostias, with its lilting accompaniment brings calmness and simplicity before the frenetic reprise of the choral fugue ‘Quam olim Abrahae,’.

The Sanctus begins with exuberance, with joyful praising of God with a fugue on the words “Hosanna in the highest.” The aria-like melody of the soloists’ Benedictus conveys the blessedness of those who come in the name of the Lord, followed by a reprise of the fugue from the Sanctus.

The Agnus Dei shifts us back to the minor tonalities of the opening movements of the Requiem. The version performed tonight is Druce’s first revision; he surmised that there must be a missing source that Süssmayr had access and has imagined what that looked like to create the Agnus Dei. When it came to publishing his completion, Novello decided that this was perhaps too fanciful, and a version more similar to Süssmayr was published instead.

The Communio utilises the music from the opening Requiem aeternam and concludes with the same fugue featured in the Kyrie, now setting the words ‘Cum sanctis tuis in aeternam’ (with Thy saints forever). Out final chord, another bare fifth, marks the culmination of Mozart, Süssmayr, and Druce’s contemplation on mortality and the afterlife. The conclusion presented is resolute yet open-ended, leaving the question of humanity’s divine judgement after death unresolved.

Samuel Foxon, March 2024

If you wish to use or adapt any part of these notes, please do get in touch!

Leave a Reply