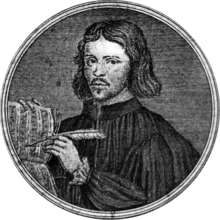

William Byrd – Struggle with the Establishment

400 years ago, the eminent English composer William Byrd died, leaving a legacy of over 470 compositions and a profound impact on the musical landscape of England. On his death the Chapel Royal described him, rather uniquely as a “Father of Musick”.

Not much is known about Byrd’s early life, with no record of his birth surviving. In 1598, Byrd writes that he was “58 yeares or ther abouts”, making the year he was born to be around 1540. Byrd was born into a relatively wealthy family, and music would have been a part of his upbringing, as both of his brothers were Choristers at St Pauls Cathedral, and his sister married an instrument maker. It is not known if Byrd followed in his brother’s footsteps, or if he instead joined the more well regarded Chapel Royal. A position at the Chapel royal would have put him with the composer Thomas Tallis (c.1505 – 1585), and there is a plethora of evidence that Tallis taught Byrd in some capacity.

Byrd spent his formative years as a musician during what could be considered the formative years of the Protestant Church of England. When Byrd was around the age of 7, Edward VI ascended to the Throne. Edward was a minor and ruled with the support of the Lord Portector Edward Seymour. With a particularly protestant leaning Privy council, the Church shifted further away from the catholic style of worship practised by Edward VI’s late father, Henry VIII (albeit the church was divorced from the Catholic church of Rome). Of great importance to the way people worshiped across the country came Royal decrees to end ‘Popish’ practices, including: reducing the use of bells in the liturgy, limiting the rite of Mass to only once per day, and enforcing the vernacular liturgy, where no Latin was said or sung (1 Corinthians XIV.19: ‘I would rather speak five words with my understanding, that I might teach others also, than ten thousand words in an unknown tongue’) Instead of incomprehensible Latin music with florid melodic lines, a syllabic approach was sought as each syllable was sung by the whole choir to aid clarity and understanding.

Byrd would have seen these compositional styles overthrown entirely when Mary I ascended to the throne in 1553, and quickly gained the honoury title of ‘Bloody Mary’ for her persecution of Protestants. Byrd would have been a teenager during this time, and would have seen the complete reversal of Mary I’s work when he was around 18. That reversal took place when Elizabeth I took to the throne, passing an Act of Supremacy proclaiming herself as the head of the Church of England. There is no doubt that she supported the protestant ideals such as the vernacular liturgy, but she seemed to have a somewhat more liberal approach to Catholic rites, perhaps in recognition of the need to unify a disparate church. Elizabeth introduced a new Prayer Book with injunctions in 1559, and much like the work of her brother Edward VI was very clear how music should be treated in the Church:

BCP, 1559

‘For the comforting of such that delight in music, it may be permitted that … there may be sung a Hymn, or such like song … that may be conveniently devised, having respect that the sentence of the Hymn may be understood and perceived’

In 1575, Elizabeth I granted Thomas Tallis and William Byrd a monopoly over Printed Music, and they used this patent to publish a publication of Latin Church music entitled ‘Cantiones quae ab argumento sacrae vocantur’ (Songs, which by their argument are called sacred), and dedicated to Elizabeth I. The two composers each contributed seventeen items to the volume, one for each year of Elizabeth’s reign. It was a daring publication, not least because of it’s Latinate nature, but also for its wide use of styles, from the older ‘Cantus Firmus’ style of plainchant, to the Italianate style of composers such as Alfonso Ferrabosco. Sadly, despite the monopoly, the publication was a financial failure. Byrd and Tallis were forced to petition Queen Elizabeth for financial help, pleading that the publication had “fallen oute to oure greate losse” and that Tallis was now “verie aged”. They were subsequently granted the leasehold on various lands in East Anglia and the West Country for a period of 21 years.

In the 1570, Pope Pius formally excommunicated Elizabeth I. The authorities in England began conflating Catholicism with sedition and treason, and thus began a period where persecution of Catholics rose. The persecutions only incited Catholicism underground to a world of priest holes and secret services. Byrd was known to be found in the company of prominent Catholics, including the likes of Lord Thomas Paget, who later was stripped of his title after being revealed as leader in several plots to instate Mary Queen of Scots to the throne. Byrd, alongside his Wife, Julianna, were often cited for recusancy (failure to attend an Anglican service), and received countless fines. Despite this, he died a wealthy man.

The Programme

This programme has been put together to serve two purposes. Firstly, to celebrate the music of William Byrd and his contemporaries, but to also show the wide variety of musical styles that Byrd was capable of writing, often subverting the established Church in the process.

The Mass for four voices was never published in Byrd’s lifetime, and manuscripts show neither the composer nor the date, to avoid incrementing the owner, as Latin Masses were effectively banned. Its performance would have been in secret. Despite being wrriten in as late as 1595, the Mass is in a pre-reformation style, and could in fact be considered as a Parody Mass. A Parody Mass is deferential to another composers work, and in this case, Byrd is modelling his work on a mass by the composer John Taverner (c. 1490–1545), using similar melodic and harmonic ideas. The Agnus Dei ends with a restless suspension figure, which expresses the text ‘Dona nobis pacem’ (Grant us peace) in manner unusual in the older style. Perhaps Byrd is asking for the peace of the persecuted Catholics with this delivery. The movements of the mass have been woven through the programme, in the order that they are performed in a traditional Latin mass.

Whilst financially a failure, Tallis and Byrd’s publication ‘Cantiones quae ab argumento sacrae vocantur’ could still be considered a musical success. Byrd’s contribution of O Lux Beata Trinitas is clearly in the Italianate style of Ferrabosco, with a florid contrapuntal style, thankfully endorsed by the very monarchy that imposed laws against complex Latin. Tallis’ contributions of O Nata Lux and Salvator Mundi are very much in Tallis signature style, although with some imitation between parts that is associated with the continental style. In both of these works, Tallis employs a technique which major and minor coincide to create a harsh dissonance, making the eventual cadence seem all the more sweeter.

Byrd enjoyed the patronage of Sir John Petre, who financed Byrd in the publication of Gradualia from which Byd’s most famous work, Ave Verum Corpus, is found. This setting combines the protestant and Catholic styles, as the Latin text is delivered syllabically, without overt floridity.

Haec Dies shows all the hallmarks of a secular piece with a sacred text, with its lively nature, and madrigal-like structure. It is also widely believed that these were the final words of the Jesuit Father Edmund Campion who was tortured and executed for his ministry to the Catholic community in England. Similarly, Alexander Briant recited the text of Miserere Mei whilst he was being martyred, giving an added poignancy to Byrd’s setting.

Thomas Tomkins (1572 – 1656) was a Welsh composer, who became a pupil of Byrd. It has been suggested Byrd facilitated Tomkins’ move firstly to Gloucester and alter to the Chapel Royal, such was Byrd’s belief in Tomkins prospects as a composer. When David Heard takes its text from 2 Samuel XVIII:33, in which King David learns that his son, Absalom, has fallen in battle. Tomkins most likely composed the piece in remembrance of Henry, Prince of Wales, who died young in 1612. The music is incredibly expressive, with a sorrowful repetition of ‘My Son’. Tomkin’s also wrote keyboard music, which will form part of this concert.

Thomas Weelkes (1576 – 1623) is quite overshadowed by Tallis and Byrd, but he was still a capable composer of the time. His secular madrigals are perhaps the most well know of his compositions. His output of church music was probably written for Chichester Cathedral, where he was organist, despite his being in constant trouble with the authorities there for drunkenness, swearing and blasphemy. Alleluia, I heard a voice, is a majestic and declamatory piece associated with Ascensiontide and Trinity.

Sing Joyfully is one of the last Anthems that Byrd wrote before his death. It is mentioned specifically by title in the program for the 1605 christening service of Mary, daughter of King James I. It would have been an apt choice of text for such an occasion with its reiteration of the ‘law of the God of Jacob’ in the final bars, which could be a subtle tribute to James I who came to the throne in 1603 (Jacobus is the Latin for James). In the work, Byrd depicts the bow strokes of the viol and mimics the call of the trumpet.

Samuel Foxon, March 2023

If you wish to use or adapt any part of these notes, please do get in touch!

Leave a Reply